Forgot your 5th Grade Civics lessons? We’ve got you covered.

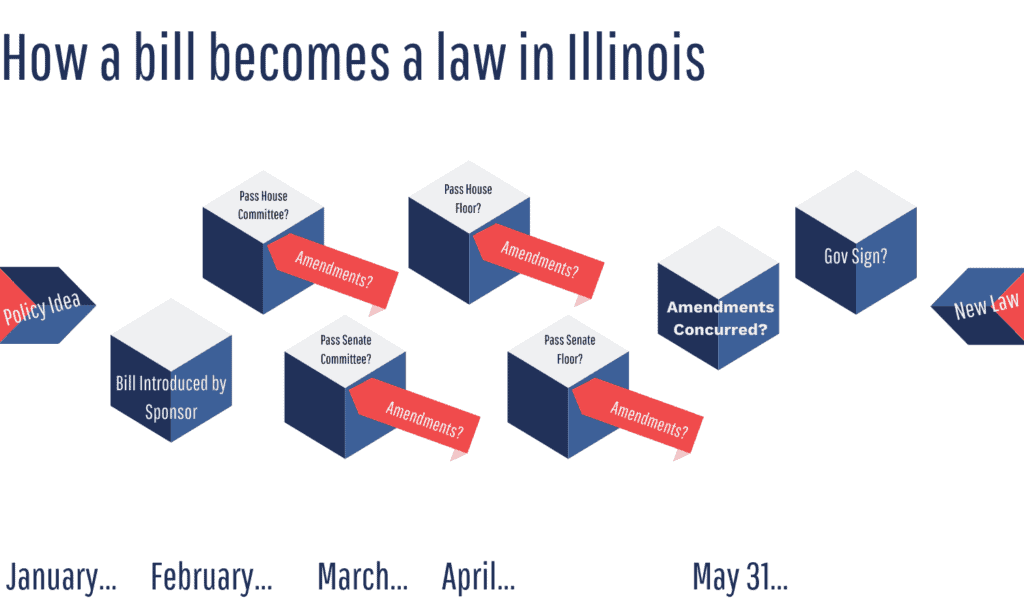

In Illinois, a policy idea becomes a bill (a formal legislative proposal), after it has been officially filed by a legislative sponsor and assigned a bill number for that session. That does not guarantee it will pass, or even get a thorough review. The sponsor must shepherd the bill through a six-month session, navigating deadlines, opposition, and the competing priorities. Every idea aspiring to become a law in Illinois has to go through at least SIX and sometimes SEVEN hurdles:

A legislator has to agree to sponsor the bill AND has to ensure all deadlines are met, and that the bill does not get “lost in the pile.”

The bill has to pass a substantive committee in the House (sponsor may amend it to get enough support to get out of committee).

It has to pass a substantive committee in the Senate (sponsor may amend, or change, the bill to get enough support to get out of committee).

It has to get 60 or more of 118 votes in the House (sponsor may amend it to get to 60 votes).

It has to get 30 or more of 59 votes in the Senate (sponsor may amend it to get to 30 votes).

(It may have to have a “concurrence” vote if any amendments were made after a vote in another chamber.)

It has to be signed by the Governor.

It is extremely rare for a bill that has opposition to pass without amendments. A good sponsor will work with opponents, supporters, and stakeholders to make smart amendments that strike the best middle ground.

A bill that does not get through these six-seven steps over the course of a session (from January through May each year) is considered finished for the year and will have to begin again. Once a bill has failed to get out of committee, it is finished for the year.

REMEMBER: A bill is just an idea! If it starts with “HB” or “SB” (or “HR” or “SR”) it is NOT YET A LAW. Laws begin with “PA.”

But what happens to bills that don’t make it? Can they come back? What happens to the bill numbers?

Think of any possible new law as an idea. It is just an idea, nothing more, until it gets filed and is assigned a bill number. Then it is a bill, an idea formally being considered by the legislature.

The legislature operates within two-year cycles, and each cycle is numbered. For example, we are now in the second year of the 101st General Assembly, meaning the legislature is assembled for the 101st two-year period in the history of our state. HB 531, the Youthful Parole Bill (signed into law in 2019), was passed on one of the final days of the 100th General Assembly, at the end of a two-year cycle.

Bill numbers are only “good” during the two-year period in which they were introduced.

For example, let’s pretend we want to file a bill to say the state must provide ice cream for every five-year-old on their birthday. We find a sponsor and they file it now, in the first year of the 101st General Assembly, 2019, and it is given the number HB 001. We work very hard, but the Cookie Manufacturer’s Association hates the HB 001 because they think the Ice Cream Manufacturers are going to get rich while cookies become unpopular. They fight HB 001, and for two years, 2019 and 2020, the bill fails. In 2021 the 102nd General Assembly begins, and we want to keep working on our ice cream birthday proposal, but now we can’t use the number HB 001. We have to start over with a new bill number because we have jumped over into a new General Assembly. Let’s imagine the only bill number available is HB 022. So now we can take the exact words from HB 001 but we need to file them with a new number, and someone else will get HB001.

This may explain why, when you look up a bill by the number, you find something totally unrelated. This may be because you have an old bill number to look up, and the proposal you care about may have a new one.